Steuben County, in upstate New York’s southwestern border, north of the Pennsylvania state line, may still have more cows than people in it.

In the late 1800s, the county built myriad beautiful truss bridges to span the quickly flowing creeks. Today Wood Road Bridge, in the Town of Campbell, is Steuben County’s only historic structure still standing and in use. The elegant 207-ft. (63 m) span graces the Cohocton River, part of the Chemung basin.

Back in 1800 the river was a busy commercial waterway every spring. Arks measuring 75 ft. by 16 ft. (22.9 by 4.9 m) transported wheat, pork venison, flour, maple sugar, black salts and pot and pearl ash to Baltimore. Today the new boat launch area by the bridge helps to accommodate recreational fishermen and people with kayaks and canoes.

The delicate, pin-connected, wrought-iron Baltimore through truss structure looks like something made with an elegant erector set. Across the single-lane deck where the timber deck now rumbles under the weight of SUVs, people on horses and in carriages once pursued their busy lives, yielding right of way, as they do now, for the one-lane bridge.

Built using a patented feature called Phoenix Columns, which were high tech in their day, Steuben County’s last remaining noteworthy bridge gained National Register recognition as a historic structure in March 2005. Visitors flocked and paddled their canoes to a grand opening when restoration was complete.

The Wood Road Bridge may really be even older than most think it is and, possibly, constructed for another water crossing. Mark Laistner, senior associate of Erdman Anthony, the engineering firm on the project, said it’s plausible that the bridge seen now may have actually been constructed someplace else, certainly not far away.

“Just looking at the bridge, you might think it was earlier than 1897. It’s just a theory because this is an iron truss bridge, and by 1889 steel had become more prevalent.” Laistner is an engineer, so it makes sense when he says intuitively, “Just looking at the bridge you think it might be earlier.”

Laistner explained it was common in the late 1800s for companies to dismantle bridges and sell them to other communities as metal rapidly replaced the original timber bridges. Whatever its origin, the Wood Road Bridge, which is delicately Victorian with metal finials and small adornments, was built at a time when old timber bridges could no longer be counted on to help America gain its commercial footing.

Construction was done by the Horseheads Bridge Company of Horseheads, N.Y., at a cost of $2,600. Worth noting, the Wood Road Bridge restoration described in this article cost $820,000 and was contracted by Vector Construction and engineered by Erdman, Anthony and Associates Inc., a company well recognized for its work with bridges, including the recent coup de grace on the Troup-Howell Bridge (now named the Frederick Douglass-Susan B. Anthony Bridge) in Rochester.

Early History of the Baltimore Through Truss

Historians might note, construction-wise, that this intact, representative example of a pin-connected, wrought-iron through truss bridge is a classic for its time. The bridge incorporates the sub-struts and tension members typical of the Baltimore truss form, which was a late 19th-century adaptation of the Pratt truss.

Distinctive, even then, was the top chord built using the patented Phoenix Columns (see The Phoenix Iron Works this page.). Manufactured by the Phoenix Iron Works, a company that even created its own town — Phoenixville, Pennsylvania — the column was a significant technological advance in the metal truss bridge construction.

Phoenix Iron Works, founded in 1783 to make iron products, made nails, then cannons for the Civil War, and eventually they came up with this column design — first for buildings — and then for use in the truss bridges. Consequently, Phoenix founded a bridge company when bridge building was booming in this country. From 1862 to 1872 great advances in bridge construction began in Phoenixville.

In the mid-1800s bridge design usually used cast iron, which is good in compression but not good in tension. The Phoenix Column, instead, used wrought iron by making a circular member out of it, which was good for both tensioning and compression.

With a superstructure with a span length of 207 ft., a width of 21 ft., and a total depth of 32 ft. (63, 6.4 and 9.4 m), it was only the floor system that had seriously deteriorated even after more than a century of use. The steel stringers had severe section losses causing a posted 4-ton (3.6 t) weight restriction. Aesthetically the paint job was poor, and safety-wise the rail system was inadequate.

Public Works to the Rescue

Beautiful pieces of our collective history — from barns to skyscrapers — disappear every day. Every piece needs its champion to let the rest of us know what peril is presented due to encroaching “progress.” The primary person responsible for rallying the troops and saving Wood Road Bridge, the last historic bridge in Steuben County, is Steve Catherman, public works professional engineer of Steuben County.

“We went back into the old atlases, which show a bridge there on what was then called Red Bridge Road,” he said. “Of the 330 bridges we maintain in Steuben County, the Wood Road Bridge is the only one left in our system that has historic value. Aesthetically, I think, it’s beautiful.”

At a recent bridge conference in Pittsburgh, Catherman learned about modern bridges in China that are multi-tiered with railroad and cars on different levels, and others that are multi-colored, but it’s the noble Wood Road Bridge that captures Catherman’s imagination.

It is certainly easier to tear down an old structure and build a new one than it is to save a historic bridge for restoration and return it to use. Prior to its revival, the Wood Road Bridge needed frequent repairs to the ever-increasing deficiencies noted during bridge inspections. It was becoming an eyesore; closure to traffic seemed imminent.

“For a time I was the only one who really wanted to save it and get it registered,” Catherman said. “Even our county administrator was favoring a more functional bridge that will unquestionably last 100 years.”

Other options discussed were a new bridge shadowing the old one, or putting in arches to strengthen it, which would ruin its integrity. Fortunately grant money from state and federal sources was obtained to cover 95 percent of the $820,000 costs for renovation (see So You Want Historic Status? page 124).

He added, “There are always some mixed feelings about getting any structure registered because, while it enhances the chances of finding funding, landmark status also limits what you can physically do to the bridge.”

Enter Erdman, Anthony and Associates

Once Steuben County decided to restore the bridge, the job went out on bid and was awarded to Erdman, Anthony and Associates Inc., a Rochester-based engineering group currently best known locally for its work on downtown Rochester’s Frederick Douglass-Susan B. Anthony Bridge. Under the guidance of Abba Lichtenstein, PE, a nationally recognized expert in the preservation of historic bridges, Erdman Anthony evaluated the feasibility of rehabilitating the bridge.

“Many years ago the person who designed a bridge would also go out and help build it. Today it is a project handed off several times before completion,” said Laistner. “Historic bridges with landmark recognition are less than routine, so that part is interesting, but they are also a pain in the neck. There are lots of constraints and lots of limitations in terms of not changing its appearance.”

Assisted by the Steuben County’s bridge crew, an in-depth bridge inspection was done to verify the geometry and condition of the old structure, which still sees plenty of traffic on it. Material samples were collected from several wrought iron components. Tensile tests were performed on samples to determine the physical properties used. Chemical and microstructure analysis were done to determine uniformity of the material. Tests confirmed that all material was wrought-iron and had similar properties.

Advanced Plastic and Materials Testing Inc. did the tensile tests to obtain the physical properties used in the analysis of the structure. Chemical and microstructure analysis were performed to determine the uniformity of the materials. A subsurface investigation done by Fisher Associates determined the foundation requirements of any potential new substructures.

A structural road rating analysis was done using a combination of finite-element and influence-line methods. The analysis was complicated by the static indeterminacy of the trusses and the presence of multiple tension-only and compression-only members. As a result, it was determined that the sub-struts and floor beam hanger members needed to be strengthened for today’s vehicular loads.

For the county, two needs were paramount: Increase the load capacity, and improve the bridge’s durability. The proposed rehabilitation work also had to pass muster with the State Historic Preservation Officer for review to determine that the project would have no effect on the historic bridge.

After this field work, the following rehab scheme was developed:

• Replace deck, stringers, and floor beams

• Strengthen 12 sub-struts

• Replace 12 floor beam hanger members

• Replace 3 lateral struts

• Cap and re-point abutments

• Rehabilitate expansion bearings

• Install new railing

• Paint the truss

Five specific features were incorporated into the project specifically addressing the historical and physical integrity of the structure. They were:

— Sub-struts needed strengthening. When the necessary cover plates were welded onto existing members, the plates were designed on structural requirements, but also in a way to minimize the changes in appearance to the members.

— Floor beam hanger members needed replacement. The existing 24-in.- deep (61 cm) transverse floor beams were replaced with new 18-in.-deep (46 cm) ones to increase the amount of freeboard available over the design flood event. In order to meet current load requirements, the hangers that support the floor beams from the middle panel points were replaced. Originally, these were square eye-bars. The new members were rods with u-bolt connections at each end. Visually the hangers are compatible with the remaining eye-bars on the bridge. Supporting the floor beams at the Phoenix Column verticals was tough because the existing u-bolts were encased in a casting and the connection pin was inaccessible. To meet the challenge a specially designed hanger connection was used. The longitudinal stringers were replaced, and the transverse timber deck. Instead, panelized, dowel-laminated, treated timber deck panels were used. A thin layer of oil and stone was used for the wearing surface.

— Lateral struts replacement. Some Phoenix tubes needed replacement. This was done by welding steel tabs onto steel pipes, in effect replicating the look of the original, patented technology. Installation of the new tubes required temporary lateral bracing and the use of a field splice in the new member.

— Protection from corrosion. Because the old floor system suffered from corrosion, the replacement of the new steel floor framing was specified to be dot-dip galvanized. A special paint system was specified for the remainder of the surfaces. Preparation included high-pressure (5,000 psi) water jetted with soluble salt-removing chemicals to remove residual chlorides from the surface. The paint’s penetrating sealer was applied to all joints and connections. The sealer neutralizes pack-rust commonly found in the crevices of structures such as trusses.

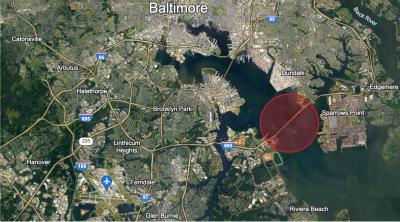

— A small boat launch (parking lot, information kiosk, and concrete walkway with steps down to the river) was added to the site, making the bridge a destination for canoeists and kayakers. The kiosk illustrates the once important use for the Chemung Basin River area for a watery trade route, which once went from Bath, with arrival about eight days later in Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay and Baltimore. Upon arrival, the cargo-carrying arks were unloaded, dismantled, and sold for lumber while the crews, presumably enriched by the journey, walked home.

Of the 330 bridges currently in use in Steuben County, Wood Road Bridge is the only one left and a structure that also merits its registration as a national landmark. Many people yielding right of way on this one-lane span may never notice the beauty of it, but to the trained eye the light metal trusses gracefully framing their crossing on the Cohocton River is a thing of beauty that can never be replicated.

Wood Road Bridge is more than a mere river crossing. The historic bridge is a piece of art, and New York State is better for it. CEG

Today's top stories